ARTICLE: A look back at 'For the Joy of Light'

When Robert Singleton's work and Dan Morro's music captivated a museum

NOTE: BELOW IS A PROFILE of the 2017-18 installation “For the Joy of Light” by Robert Singleton and Dan Morro, at the Huntington Museum of Art in Huntington, W.Va. The story offers insights into Robert’s life story and artistic journey, as well as capturing the ambitions and power of the impressive installation at the museum. | March 6, 2023

This story first appeared in the Aug. 12, 2017 Charleston Gazette-Mail

By DOUGLAS JOHN IMBROGNO

Total darkness.

That is how the Huntington Museum of Art’s new multimedia exhibit, “For the Joy of Light,” begins. There are a couple of ways to look at the opening of this exhibit, which promises light but starts off in inky blackness. Most obviously, not being able to look at anything when you first enter into an exhibition provides for sheer drama.

“It’s not the standard museum presentation, where you walk in and see one painting after another,” said Robert Singleton, whose work is featured in the exhibit, on view through Feb. 4, 2018.

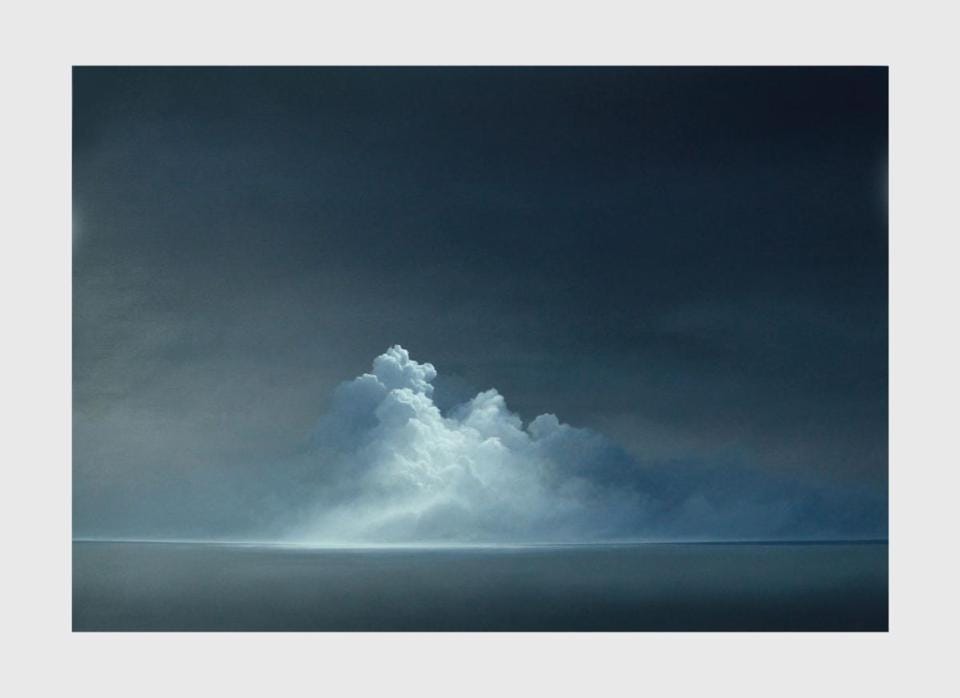

On the way into the darkened space, you pass two barely lit canvases featuring the startlingly simple, yet minutely detailed and illuminated clouds Singleton has painted, on and off, for years. But once in the center of the main hall, you stand in darkness, facing a black wall.

Then a soundscape commences by Singleton’s collaborator on the exhibit, German musician and composer Dan Morro. As the room begins to fill with interweaving threads of harmonic sounds and multilayered vocals (sung by Morro), high-tech lighting — almost imperceptibly at first — reveals the dim outlines of a triptych of distant clouds on a gray-blue horizon.

As the light brightens, the clouds come into vivid, detailed focus. Yet because of a carefully calculated interplay between light, paint and canvas, Singleton’s clouds don’t appear to be flat images. It’s as if they are three-dimensional entities. Instead of looking at paintings on a wall, it appears you are looking outward, at distant clouds through picture windows.

Or perhaps a dreamscape.

Inner Sanctum

TAKING A PAUSE ONE DAY from preparing the exhibit, Singleton and Morro spoke of its birth and how their creative lives crossed paths across an ocean.

“It’s like an inner sanctum almost, like something dark but also something holy that you walk into,” Morro said.

“You’re surrounded by these large works, and it’s a bit frightening. But at the same time, it’s a positive feeling when the light comes up and kind of reveals the things that you’re actually surrounded with.”

Then the light dims on the clouds in front of you and comes up on more Singleton paintings on the opposite wall. These are not clouds, but large, evocative geometric shapes viewers turn to face and absorb as they materialize out of the dark.

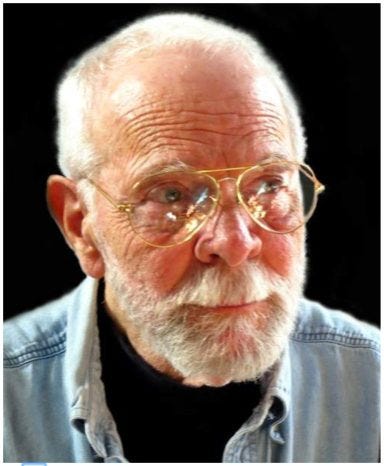

Yet aside from its carefully plotted multisensory presentation, there is another way of looking at “For the Joy of Light.” The story of the exhibit’s creation encapsulates how the light went dark on 79-year-old Singleton’s acclaimed work.

And how a 39-year-old German musician found Singleton’s work on the internet and played a role in turning the lights back on.

The arc of Singleton’s career is told in several places online, including about how he came to live on a mountaintop in rural Hardy County in 1979.

Singleton had a notable international career as a younger painter, an abstract expressionist in the vein of Hanz Hoffmann. That was several decades ago.

Then he found he had no more to express.

“I’d reached a point with one painting and thought, ‘This is as far as I can go with this’ — this wild, emotional, organic brush stroke and color, put in juxtaposition to a hard-edged square,” he said.

Realizing he had hit a wall in his career, he fell into a three-day funk. On the third day, he took a walk with his dog. At one point, he lay back on some grass and nodded off. He woke up.

His depression was gone. He realized what he wanted to paint moving forward.

Clouds.

“Clouds are the perfect organic shape,” Singleton said.

He and Morro sat in a Huntington Museum office after tweaking the exhibit’s special Smithsonian-quality lights for the hundredth time.

“You’ll never find two that are the same. Creating them is really fun,” Singleton continued. “Over the years, as I’ve developed my craft, they are basically vehicles for capturing light in the atmosphere.”

Morro spoke up.

“So basically, you decided to paint light. And the clouds were just, like, the vessel,” he said.

“Exactly,” Singleton said.

The Source of the Light

AT SOME POINT, Singleton met Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, whose influential book, “On Death and Dying,” helped bolster and grow the modern hospice movement.

Kubler-Ross once remarked about Singleton’s cloud paintings. She wondered about the source of light that animated his seemingly simple cloud depictions, which made viewers reflective and introspective — mesmerized, even.

The light illuminating each cloud seemed to be coming from just behind the next painting over, she told the painter.

Singleton recalled what Kubler-Ross asked next.

“She said, ‘Do you think you’ll ever paint the source of the light?’”

He responded quickly: “Oh, no! I’m not good enough to paint the source of the light,” he told her.

An attendant had driven Kubler-Ross from her Virginia residence to Singleton’s Hardy County home that day.

The driver, catching Singleton alone later, said she had to share with him a remark Kubler-Ross made to her about the artist’s work.

Kubler-Ross said, “He has already seen the light. And he doesn’t even know it …”

Singleton, who has the countenance of a short-bearded Santa behind aviator eyeglasses when he laughs, grinned merrily at the memory.

“Which was a really fine compliment,” he said.

They became close friends.

He trained with Kubler-Ross in compassionate care for the dying. Starting in 1985, Singleton served for a decade on the board of directors for her center. He met her just as the tendrils of the HIV-AIDS crisis were beginning to grab the gay community and strike fear into the hearts of families, towns and cities worldwide.

Kubler-Ross saw it coming, Singleton said.

“She was such a visionary in that she said, ‘This is going to become an epidemic. And the world is going to need real caregivers because the medical profession will not be able to handle the scope and number of sick people.’”

Singleton became one of those trained caregivers, even as his own friends and lovers began to grow sick and die.

His losses were inestimable.

“Without question — all of my lifelong friends. Every single one of them. My best friend who was like a brother …”

Many wanted him there as death approached, he said.

“They knew something was different about me. And they felt comfortable with me. And I helped them over,” he said. “They wanted me to do that.”

On his Hardy County property, beneath an old tree, rest nine headstones, marking the lives of nine friends. Not all died of AIDS, but all asked that their ashes be sprinkled beneath the tree, within sight of Singleton’s adopted home in the West Virginia hills.

Hollow

HIS ENCOUNTER WITH KUBLER-ROSS transformed him in more ways than one.

“She was, without question, the single person in my entire life that changed it,” Singleton said.

In what way?

“Much more accepting of myself with love. And not feeling the necessity to hide who I am,” he said.

But years of long days and nights caring for the dying had taken a toll on the artist. It had left him, he said, choosing the word carefully, “hollow.”

“I put so much into caring for these people. The big question was, ‘I just want to do the right thing for them.’ So that was my mission,” he said.

He was done.

As for his painting — clouds or otherwise?

“I was getting old, sorry to say that. And I had lost all my friends. And I had, frankly, just given up.”

‘How Can This Be?’

DAN MORRO GREW UP in a small village in East Berlin.

After the Berlin Wall fell, he enthusiastically launched a country-leaping caravan of bands and performances.

These included Scandinavian-influenced metal music with a band called Obscurity. The indie electronic band Ortega. The hip-hop influenced D.O.G.z. The techno-scene group Funkwerkstatt. And a self-produced solo project, “i Am Halo,” among other projects.

Beholden to no genre, it would not be a difficult leap for him to jump to being a soundscape collaborator.

While still in Germany, he stumbled upon Singleton’s website. He left a message for the painter.

Seeing his work — the cloud paintings especially — he could not fathom that Singleton had given up on exhibiting for almost a decade.

“I thought to myself, ‘How can this be?’” Morro said. “And, ‘Why is that? What can I do?’”

They emailed. Then they Skyped.

Then Morro came to America, to the remote Hardy County home where Singleton had retreated from the noisy, busy world of art openings and career making.

“I felt like there was a connection that I made instantly to his art, but also to his spiritual way of being in the world,” Morro said.

And he strongly felt Singleton’s work was needed back in the world.

“Because I think the world can be such a sucky place,” Morro said.

“I mean, you know, no offense, but I see so much art out there that’s just about being crazy. And being super awkward and different and ‘Look at me!’ kind of art and music.

“What Robert does is so deep and so full of soul and — I don’t know — full of life energy. And also full of hope.”

Morro paused.

“I wanted nothing more than to see him basically bring his gift out there again and share it with the world. And not just sit on his mountaintop with all his art by himself,” he said.

Morro laughed, looking over at Singleton.

“Maybe that’s not the way it totally was. But that’s how I perceived it,” he said. “I said to Robert — ‘OK, if I make this work, can we do this together?’”

‘You’re Not Finished!’

BUT HE HAD NO NEW WORK to show, he told Morro, the voice of the sensible, retired, too-old artist.

“Dan, who was such a motivator, said, ‘No no no no no! You’re not finished! You have too much to give.’”

“I said, ‘Well, in order to have a show, I have to have a body of work,’” Singleton recalled.

Then, get to the studio, said Morro.

It was the summer of 2013. By summer’s end, Singleton had completed a half-dozen large paintings. Morro had composed five songs on his laptop.

In 2014, Singleton pitched the idea to the Huntington Museum for the collaboration that would become “For the Joy of Light.”

“So this project is three years in the making,” he said.

Singleton employed an ancient art world concept to describe the role Morro played in new work leaping from a West Virginia mountaintop and into the wider world.

“We talk about ‘the muse’ sometimes,” he said. “He certainly served as a muse.”

For his part, Morro said, he was happy to see Singleton’s work available again, to be experienced by people who had never witnessed it before in person.

“It’s more about that spiritual part, the power that is in there,” Morro said. “The contrast of dark and light. The certain place that it takes you to.

“I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s kind of what the world needs.’”